NOTE FOR THE VISUALLY IMPAIRED: This story is also available as an audio recording, read by Kat, the author.

You are about to read a section from the middle of my memoir, Pet Tracker. To read the FULL Substack version (for free!) from the very start of the book, go to this link, scroll down until you see the “See All >” button, and click on it. Then, scroll all of the way to the very bottom, and you can start reading the beginning of the book with the “Dedication & Introduction.”

If you missed the previous Pet Tracker story that preceded this post, you can find it here.

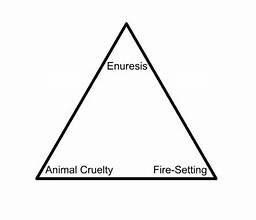

In homicide investigations, there’s a combination of three seemingly unrelated behaviors that investigators call “the homicidal triad.” Identified by the FBI after interviews with more than three hundred and fifty serial killers, it says, in a nutshell, that if you have an adolescent white male who displays three behaviors—cruelty to animals, fire setting, and bed-wetting beyond an appropriate age—that this combination may be a precursor to homicidal tendencies.

Thankfully, it doesn’t always work that way. In his book The Anatomy of Motive, author and former FBI-agent John Douglas acknowledged that not every boy who displays the combination of these three behaviors will grow up to be a killer. But Douglas added, “The combination of the three was so prominent in our study subjects that we began recommending that a pattern of any two of them should raise a warning flag for parents and teachers.”

It was theories like the homicidal triad and the dozens of others I had used in law enforcement that got me thinking about how I could assess the behavior of lost pets and somehow find a way to predict what they were going to do next. As with the FBI theory, there are few hard-and-fast rules in any investigation, but there are lots of theories that can make it easier to look at a case more objectively, and that helped me bring cases to resolution.

I started out by looking for a general formula that could be applied to any missing pet. In each missing-pet case, I discovered that there were three interrelated behaviors that played a critical role in whether the pet was recovered: the behavior of the pet, the behavior of the owner/guardian, and the behavior of the person who found or recovered that pet.

What the people (the person who lost the animal or the person who found the animal) believed influenced how they behaved. For example, if the guardian believed that their cat was killed by a coyote, they’d often refuse to conduct any type of physical search for their cat since they believed it was dead. If an indoor-only cat with a skittish temperament escaped outside and was seen by a neighbor darting and hiding under their deck, they’d assume the cat was an unowned “feral” cat.

And finally, rescuers who found a dog in a rural area would often assume that the dog was “dumped” there, never realizing that the dog they found could be a lost dog, even one involved in a rollover car crash with a team of people searching for it, and just happened to be trotting through that rural area.

Even more interesting to me was that this same behavior—a skittish temperament—was interpreted differently when seen in dogs and in cats. People who saw a dog that was skittish would assume that abusive treatment of the dog was responsible for the fearfulness. They just assumed that the dog was physically abused because of how terrified it behaved. And people who saw a cat that was skittish would assume that a lack of tameness of the cat was responsible for the fearfulness. They assumed the cat was feral. People will see the same fearfulness but in dogs its blamed on “abuse” and in cats it’s assumed to be an unowned, “feral” cat.

The result of the misinterpretation of behaviors in both dogs and cats has led to a common problem that skittish dogs, when they are captured, are often rehomed to a new “forever home” instead of rescuers searching for the dog’s actual home. This happens because, in many cases, rescuers see the fearful behavior and just assume that whoever previously owned that dog abused it and “doesn’t deserve” to get that dog back. Many families hearts have been broken because they never see their missing dog again.

With skittish cats, it’s a bit different. The majority of escaped skittish, indoor-only house cats that are not found by their family are typically left to live in feral cat colonies or survive in neighborhoods as what animal shelters now call a “community cat.” That is where a cat has no official family but often various neighbors will feed it. The saddest part of skittish cat behavior is that so many skittish, house cats are assumed to be feral, humanely trapped, and taken to animal shelters. If they’re lucky, they will be adopted out as “barn cats” where they can live off of catching mice on a ranch, otherwise the majority are just euthanized. My previous (amazing, tear jerker) story of the cat J.B., who shelter staff assumed was feral because of his behavior, is a prime example.

In the bestselling book, “The Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Know, and Smell” author Alexandra Horowitz explains that dogs have different threshold levels (seemingly related to the amount of phot receptors in their eyes) to the stress hormone cortisol. These different thresholds create different reactions to stimuli. A rabbit that bolts in front of two different dogs produces the same amount of stress hormone, but if the dogs have different threshold levels, it will create a different response. A dog like a Bulldog with fewer photo receptors and a high threshold level might just stand there and watch the rabbit while a sighthound like a Whippet that has many more photo receptors and a very low threshold might take off in a full-on chase!

Companion animals that have an extremely low threshold are easily triggered into the “fight or flight” mode. That’s because the brain will signal the release of an excessive amount of the stress hormone cortisol that courses throughout their body when they are triggered. And one of the most common ways that skittish, loose dogs are triggered to take off running from would-be rescuers is when those people look directly at the dog, walk directly towards the dog, call out to the dog, clap their hands, or whistle at the dog.

Besides confirming that dogs can be trained to find lost pets, one of the greatest discoveries that I made that has resulted in countless panicked dogs from being recovered and brought to safety is the use of “calming signals,” a technique discovered by Norwegian dog trainer Turid Rugass. The signals are physical actions that dogs use, in hopes of avoiding a canine kerfuffle, to communicate to another dog that they are calm and are not a threat. Turid taught calming signals to other dog trainers so they could interpret a dog’s behavior, understand when a dog is stressed, and even calm the dog by demonstrating one of these signals to a stressed dog. Examples of these signals include when a dog yawns, wags his tail in a low and slow motion, avoids making eye contact, or licks his lips.

It made sense to me that if a rescuer were to encounter a skittish dog that was clearly ready to bolt and run, perhaps that rescuer, too, could change their own body language and communicate to a dog that they were not a threat. I began to test my theory with every stray dog that I encountered by immediately sitting down on the ground. I did this because it only made sense to me that sitting on the ground was less threatening to a dog than a standing human. I figured it also might spark a memory in the dog of when his family members, especially small children, sat down and played with that dog when it was a puppy.

In some cases, the dog would come to me but in many cases, it would just stop and watch me and wouldn’t come closer. So, I started using some of Turid’s techniques. I would not look at the dog, but instead I would turn my face towards the ground and watch the dog from the corner of my eye. To the dog, it looked like I was ignoring him or that I didn’t notice him. This worked in a few cases, but still many dogs refused to come all of the way up to me.

I perfected the technique when I added yummy treats along with sounds associated with eating food. I’d put cut up small pieces of hot dog, put them inside an empty potato chip bag, and while ignoring the dog (with him interpreting that I was looking at the ground and not at him) I’d fake like I was eating from the bag while I made crinkling sounds with the bag. And when I started to toss pieces of hotdog towards the dog while I made obnoxious “mmmmmm…nummy, nummy, nummy…mmmmm” lip-smacking sounds that I’d previously used at home to tease my own dogs, it worked like magic!

I recovered countless loose dogs with this technique and ultimately taught it to my pet detective students, pet rescuers, animal shelter staff, and even animal control officers. I also made a calming signals YouTube video that is widely shared with dog owners by pet rescuers involved in lost dog recovery work across North America.

Here’s my Calming Signals video: